A long time ago in a galaxy far, far away….

there was this star that, by all known theories of stellar evolution (the study of how stars are born, live and die), should have died. Many stories in the media lately have described this star as the “Zombie” star since, contrary to what should have happened –that it should have died, it came back to life much like a “zombie”. It is, by all accounts, the astronomical analog of a horror film character: a star that just wouldn’t stay dead.

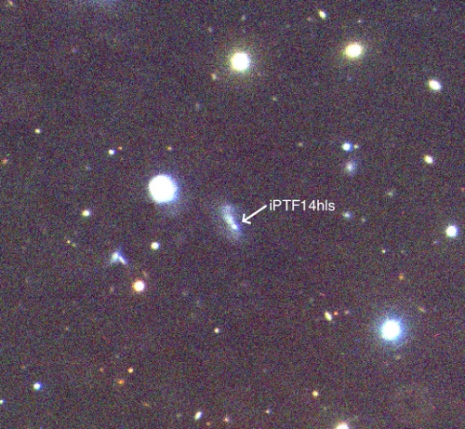

Located in the constellation of Ursa Major, The Great Bear, astronomers first detected a supernova outburst in a distant galaxy (see discovery image above), an object so distant that its light we see today left it long before the Age of the Dinosaurs began, about 500 million years ago.

The “Zombie Star” is a rare type of supernova and is located on the sky in the constellation of Ursa Major at the location indicated by the white star.

All stars produce energy by changing lighter elements into heavier elements. This process begins in all cases with four hydrogen atoms being converted into one helium atom and continues throughout the star’s lifetime, ending when most of the hydrogen in the star’s core has been consumed. In the case of stars like our sun, using the helium that has built up during the star’s “normal” lifetime, the process continues its energy production, producing carbon and oxygen as byproducts. Stars are thus huge elemental factories, the only sources of heavier elements, the elements necessary for new planets and life itself. It is often said and is quite true that we are all made of star stuff; this sentiment is quite prosaic but also, quite true.

For stars larger and more massive than our sun, the star’s fate is quite different. For these more massive stars, the process doesn’t stop with helium but continues all the way up to and including the element silicon (the same element that makes up the sand on our beautiful beaches and quartz crystals). This stage of a star’s evolutionary life cycle only occurs for stars at least ten times more massive than our sun and produces heavy metals up to and including iron and nickel. This is the end state for all stars, regardless of how large and massive they are. What comes next, a nuclear dead end and the logical end state in the star’s evolutionary life cycle, is what astronomers call a “Core Collapse” supernova. At this point, no more energy can be produced and the star’s nickel-iron core, quite literally, collapses in upon itself, producing an enormous explosion, obliterating the star and everything within 10 light years (a light year is the distance light travels in one year). Astronomers believe the “Zombie Star” is a rare form of this type of supernova.

The light outburst of a core collapse supernova generally lasts about 100 days. In the case of the zombie star, an outburst was first observed in 1954 and then again in September of 2014. In the intervening sixty years, no light was observed where it was first observed in 1954; this observation is inconsistent with all known models of supernova explosions and thus, the mystery remains. Some astronomers believe the star is unusually massive, more than 120 times the mass of the sun and, because of this enormous mass, its core survives intact even after the supernova. Closer to home, a star similar to such a massive star is Eta Carinae, located in the southern hemisphere constellation of Carina, a ship’s keel and formerly part of the larger constellation Argo Navis. This star has survived in spite of several outbursts equal in power to a small supernova over the last three decades.

A close to home look at what the zombie star might look like. Eta Carina, as imaged here with the Hubble Space Telescope, is a supermassive star in our own galaxy that has survived at least two known outbursts equal in power to a small supernova. This image is also presented as the “Featured Image” for this article. Imaged credit: NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope and STSci.edu (Space Telescope Science Institute).

We will always find that there will be more questions than answers the more we explore and discover; this is simply the nature of science and discovery. In the case of the Zombie star, continued study of the data and how it compares to our models and theories on stellar evolution is warranted. True science demands that our theories and ideas evolve and change as new discoveries are made and that they always conform to the data, never the reverse. Just when we think we can finally declare the science as settled, something new and exciting is discovered – this is the way it always has been and is how authentic progress is made. By building on what we know, discovering something new and answering one question at a time, slowly do we advance our understanding of the universe and our place in it. Isaac Newton, perhaps one of the truly brilliant minds to ever have lived, said with a profound humility near the end of his life: “If I have seen further it is only by standing upon ye shoulders of giants“. And so thus, we continue ad astra per aspera (to the stars with difficulty)!

For those who are interested, the original, peer-reviewed article on the star that would die can be found here.

Buy us a Coffee? https://www.buymeacoffee.com/astronomychange

Follow Us On Twitter: https://twitter.com/astronomychange

Why not support us on Patreon: https://www.patreon.com/astronomyforchange