In death, comes new life. In the grandest example of the Cycle of Life, the death of a massive star provides the raw materials for new stars, planets and life!

This article was originally published in Substack

We, bound by a common origin, composed of elements forged in the nuclear cauldrons of long-dead stars, look up at the stars and, in humility, connect with each other. (James Daly, Ph.D).

WR140

During the winter months, with the highest number of bright stars visible of any season, the brilliant jewels of winter, it is fitting to consider the sage words of the late, great Carl Sagan so eloquently spoken in his Pale Blue Dot. As we look upwards towards the brilliant jewels of Orion, brilliant Sirius beckoning and know that there are others too who are gazing as we are; that this is the nexus that binds us all together, the oneness with that great canopy of stars above, fellow travelers upon this beautiful blue miracle in orbit about our home star.

Located 5,300 light years distant in the Northwest Quadrant of Cygnus is WR140.

Following Astronomical Twilight and looking to the northwest, highlighted by the blue-white star Deneb, we see Cygnus the Swan or, as it is colloquially referred to, the Northern Cross, as it sets. Cygnus is a constellation prominent during the summer months in the Northern Hemisphere and will be out of view shortly as we head into deep winter.

So, what is WR140?

WR signifies that the object is a Wolf-Rayet star, a 10-solar mass star nearing the end of its life and the brightest such star in the Northern Hemisphere. It is in a rare and particularly extraordinary evolutionary phase and one of only 600 such stars catalogued in our Milky Way galaxy.

Video of WR140 and Environs

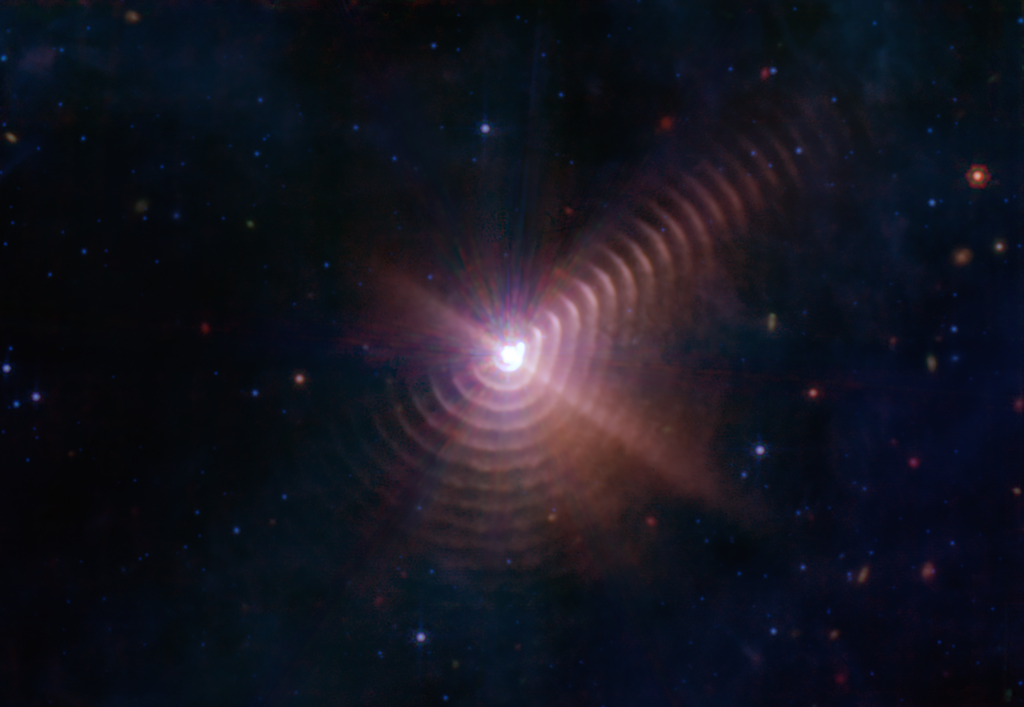

WR140 as imaged by JWST, revealing the extraordinary carbon dust shell structure, a new layer added every 8 years as its massive binary companion pass it within one AU!

Time lapse animated image of WR140 in the mid-infrared, illustrating the evolution of the carbon-dust rings. This imaged by JWST’s MIRI instrument was produced over the course of a year between 2022 and 2023…

Discovered by their distinctive spectra by French astronomers C.J. Wolf and Georges Rayet in 1867, many present without any hydrogen in their spectra and all, with broad emission lines of ionized Carbon, Nitrogen, Oxygen and Silicon. It’s highly unusual for a star to exhibit emission spectra. This happens when a gas is ionized (by ionizing radiation such as Ultra Violet light, which WR stars produce in abundance). Oxygen and Silicon are elements produced during late-stage evolution of high-mass stars.

Classic Wolf–Rayet stars have completely lost their outer hydrogen shell and are fusing helium or heavier elements in their cores. Lasting only 24 hours, Silicon burning is the last evolutionary stage in any star’s life and represents the death knell for the star.

All stars begin their lives producing energy through hydrogen fusion reactions in their cores. This process produces helium and a lot of energy. When the star’s initial complement of hydrogen has been reduced to about 12% of its original mass for stars like our sun, the star will expand to become a red giant and transition to helium burning. For stars in the mass range of the sun, the process ends here with the formation of a planetary nebula and a carbon-oxygen White Dwarf core.

How far along and how many successively heavier burning cycles a star can sustain depends on its initial mass when it formed. For the sun, the path is rather short, concluding with helium fusion and a carbon-oxygen white dwarf star. For stars greater than 10 solar masses, heavy-element nucleosynthesis continues and ultimately ends with silicon burning.

Once silicon burning begins, with the core temperature soaring above 3 billion degrees Kelvin, the supernova clock starts ticking. In the end, the endothermic property of iron prevents the newly formed iron and nickel, built up in the core and the byproducts of Silicon fusion, from producing any energy and, thus, all energy production ends with the conclusion of silicon burning and, with it, all outward support.

With nothing left to sustain outward pressure against gravitational collapse, the outer core immediately implodes at 20% the speed of light onto the newly formed and now degenerate nickel-iron core. The shockwave rebounds, propagating outward at supersonic velocities, obliterating the star in spectacular fashion as a Type II, core-collapse supernova! Depending on the original mass of the star, a neutron star or black hole will remain.

In the Grandest example of The Cycle of Life, the expanding supernova remnant will enrich the interstellar medium with the raw materials for new planets, stars, and life!

The Hottest Stars in the Universe

With photospheric temperatures between 20,000 K and 210,000 K (that’s not a typo — that is two hundred, ten thousand), Wolf-Rayet stars have the highest temperatures of any stars in the universe. For some and as another unique and distinct identifier, they present without hydrogen in their spectra. Why?

The furious stellar wind originating in the cores of these monsters pushes off their outer layers of gas, exposing the fusing core! WR140’s photospheric temperature is measured at 70,000 K! It is important to identify where this temperature is measured.

Unless otherwise mentioned, stellar temperature generally refers to the photospheric temperature. For any star, even stellar misers such as the lowest-mass Red Dwarfs, in order to instantiate hydrogen fusion ignition in the core, a minimum temperature of 10 million Kelvin is required. This is generally understood, so references to temperature is to the photospheric temperature. Stars have no solid surface as such, so the photosphere is the star’s “disk”.

The following image of WR 31a, located about 30,000 light-years away in the constellation of Carina, illustrates a Wolf-Rayet stellar bubble, the ejection of the star’s outer shell of hydrogen and helium. The expanding blue outer shell is the expelled hydrogen and helium of what used to be the star’s outer layers, while the remaining photospheric disk burns at over 100,000 Kelvin.

Located about 30 000 light-years distant in the constellation Carina, WR31a is immersed in its bubble of hydrogen and helium. This nebula is the ejecta that was once the outer gas shell of the star. The central star burns at over 100,000! Image via the Hubble Space Telescope, NASA and StSci.edu.

Classification

Wolf–Rayet stars were named on the basis of the strong, broad emission lines in their spectra, identified with helium, nitrogen, carbon, silicon, and oxygen, but with hydrogen lines usually weak or absent, as described above.

The three principal types of Wolf-Rayet stars are:

- WC, strong carbon emission lines (the classification for WR140 is WC7);

- WN, strong Nitrogen emission lines;

- WO, strong Oxygen emission lines. These stars are the hottest WR stars. Generally, the heavier the nucleus, the more energy is required to ionize the atom. Oxygen is heavier than Carbon and Nitrogen. For this reason, WR stars exhibiting Oxygen emission lines are generally hotter than the other two principal types, WC and WN. To wit:

- Oxygen is the heaviest of the 3 nuclei, containing 8 protons. It thus, requires a greater energy and thus, higher temperature, to ionize and,

- The presence of fresh oxygen in the spectra suggests that Oxygen, a product of predominantly Helium burning and, alternatively, Carbon burning, is being produced.

Carbon Dust Shells

Through the dynamic interplay between each star, a complex series of cabon-rich dust shells is being created at regular intervals as the stars pass each other every 8 years. According to Emma Lieb, the lead author of the new paper and a doctoral student at the University of Denver in Colorado:

“The telescope not only confirmed that these dust shells are real, its data also showed that the dust shells are moving outward at consistent velocities, revealing visible changes over incredibly short periods of time,”

As the stars swing past one another, the stellar winds from each slam together, the material compresses, and carbon-rich dust forms. The latest observations show 17 distinct dust shells shining in mid-infrared light that are expanding at regular intervals into the surrounding space at 2600 km/sec or velocities approaching 1% the speed of light!

Will WR140 end in a Type-II supernova, and why is it so unique?

The furious stellar winds of these stars, ejecting vast amounts of enriched material into the interstellar medium, play a crucial role in the chemical evolution of galaxies, seeding the interstellar medium with heavy elements essential for planet formation and life itself. As gifts that keep on giving, WR stars are generally considered to be supernova candidates. As these stars age and evovle, they begin to eject these vast amounts of enriched material described above. The Wolf-Rayet phase of a high-mass star’s evolution is considered to be the last stable point before the star’s spectacular demise as a Type-II, core-collapse supernova and are regarded as ticking time-bombs.

So, will WR140 end its life in spectacular fashion as a Type-II core-collapse supernova?

The short answer is yes. WR140 is well on its way now, having completed hydrogen burning and, based on the active production of a compression-induced, carbon rich environment described above, is well into its Helium-burning phase now. To wit:

- the regular and continued production of the carbon-rich dust shells, clearly imaged by JWST and

- that WR140 is a WC(7) type Wolf-Rayet star, presenting with strong ionized carbon and oxygen emission lines.

Not only will these stars meet their demise as Type-II supernovae, both WR-104 and WR 140 are stripped-envelope, Type Ic progenitors, both of which could theoretically produce Gamma Ray Bursts if they collapse into black holes and have the right rotation and alignment.

In addition, it’s high-mass companion, a 30-solar mass, O5.5 evolved behemoth, a blue giant or supergiant star, is also a supernova candidate. According to the published study, however, WR140 is the more evolved component of the binary system and thus, will explode first as a supernova.

So what will become of the star that remains?

With an orbital period of 8 years for the binary pair, a periastron (closest approach) of 1 Astronomical Unit (the Earth-sun distance) and apastron (furthest distance) of 3 billion kilometers (distance to Neptune, 24 AU), the companion’s distance from WR140 will play a role in what happens to it. We can look to SN1987a, the closest Type-II supernova extensively observed in modern times for guidance.

1. Survivability of the Companion

- Given that WR 140 is significantly more evolved, it will likely be the first to explode as a core-collapse supernova (possibly forming a black hole or neutron star as a remnant).

- If the explosion is asymmetrical (off axis), the companion star could be ejected from the system due to a sudden change in gravitational balance.

- If the explosion is more symmetric, the companion might remain bound, though the system could shift to a more highly eccentric orbit around the remnant, a black hole or neutron star.

2. Impact of the Supernova on the Companion

- The O-type companion will be exposed to a blast wave, radiation, and ejecta. Given its large mass (~30 solar masses), it could survive but may suffer:

- Mass loss due to ablation (forced removal of material) from supernova ejecta.

- Changes in rotation and surface composition due to supernova-driven shock waves.

- Stripping of outer layers, affecting its further evolution.

3. Potential Outcomes

- If the companion remains bound to the black hole/neutron star remnant, it could become a high-mass X-ray binary, accreting material from stellar winds.

- If it is ejected, it will become a runaway star, speeding through the galaxy at high velocity.

- If the WR 140 explosion triggers a hypernova or gamma-ray burst, the radiation might significantly impact the companion, possibly disrupting its structure or even leading to partial mass loss.

4. Future Supernova of the Companion

- With a life expectancy of less than 10 million years (compared to the sun’s of 10 billion years), the O-type star is also a supernova candidate but may take longer to explode.

- If it remains gravitationally bound, the second supernova might disrupt the binary system completely, leaving behind either two compact objects (black holes or neutron stars) or an eventual black hole merger.

The most probable outcome

- the companion star will either:

- Survive but be ejected as a runaway star due to the loss of gravitational binding.

- Remain bound to a compact remnant, possibly leading to an X-ray binary or later black hole merger.

- Sustain damage from the explosion, altering its evolution but continuing its life cycle toward its eventual supernova fate.

We’ll just have to wait and see. Like the star Betelgeuse that was recently thought to be on the verge of going supernova, there is really no way to predict precicely when the event will happen. It likely hasn’t happened yet as the star is still in its later helium-burning phase. Having said that, each successive heavier-element buring cycle is dramatically shorter than the previous. WR140 is a 10-solar mass star. A star in this mass range has a life expectancy of less than 10 million years, most of which as a main-sequence star in its hydrogen-burning phase.

A Threat to Life on Earth?

We recently published an article about WR-104, a similar WR star in Sagittarius. Like WR-140, WR-104 is also a WC (strong carbon emission lines) Wolf-Rayet star. Both stars have a stripped-envelope, a powerfully-emitting hydrogen and/or helium shell or envelope, sitting above the active core. The enormous radiation pressure produced by the core has elevated the star’s outer layers, exposing the active, fusing core.

As discussed at length in our previous article, when in doubt about the characteristics or properties of an object, if you can see it, believe what what you see with your eyes. Take note of the highly coincentric carbon dust shells produced by WR-140 as revealed by JWST. Their coincentricity, almost-circular morphology and consistently-spaced separation suggests the system’s polar axis is tightly-aligned with with our line of sight with a vanishingly small angle of inclination, perhaps more-so aligned than WR-104!

It is also 3,000 light years closer to us than WR-104 at 5,300 light years!

So, with all the concern about WR-104 and its potential lethality, we should consider WR-140 in the same way.

As stated exentsively, it is almost impossible to predict exactly when a star will explode as a supernova. There are some external markers such as the development of powerful stellar winds and the consequent expulsion of material, dimming (as was the case with Betelgeuse) and/or, a significant change in size but, other than these, we’ll just have to wait and see.

If WR-140 goes supernova today, our descendants 5,300 years hence will see it as a brilliant new star in the Northwest quadrant of Cygnus. If it exploded 5,300 years ago, then we’ll see it very soon. In either case, when we do see it (with visible light), we will, at the same instant, be exposed to a dose of gamma rays on a planetary scale, a dose, at this point, of unknown strength or duration.

Colliding Wind Binary

This binary system is now regarded as the prototype for a new class of binary star system, a colliding-wind binary, in which the two member stars are massive stars that emit powerful, radiatively-driven stellar winds.

Additional sources

Published study in The Astrophysical Journal letters (2025 January 13)

https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.3847/2041-8213/ad9aa9

NASA/James Webb Space Telescope Carbon Rich Dust Shells

Image and video content from the mission and the study

https://webbtelescope.org/contents/news-releases/2025/news-2025-103#section-id-2

Please see my latest post in Substack here.

A quick, interactive web-based version of Stellarium is available here Tonight's Sky. When you launch the application, it defaults to north-facing and your location (on mobile and desktop).

Astronomy For Change: https://astronomyforchange.org

Did you enjoy this article or like what we do? Why not leave a tip or buy us a Coffee?

Follow Us On Twitter: https://twitter.com/astronomychange

Why not support us on Patreon: https://www.patreon.com/astronomyforchange

Imagination is more important than knowledge

![]()

An index of all articles can be found here.

If you enjoyed this article, please consider supporting us with a modest donation

or through a subscription on our Patreon Page

Membership at Astronomy for Change is Free!